Madder Movie: Anime and Moe in Contemporary Japan

May 12, 2017

by Sebastian Choe, Columbia University

Originally published in the 2017 edition.

Preface

This paper functions as a companion piece to my experimental short film, Madder Movie (2016). The paper will decode the questions and concepts that the film investigates, and its organization will mirror the organization of the film, divided into four “steps.” Madder Movie runs four minutes in length, compositing original and found footage, animating video game screenshots, and navigating through a 3D-modeled environment with a soundtrack of contemporary electronic music synchronized with the film.¹

I. Introduction

Madder Movie first and foremost investigates the contemporary Japanese phenomenon of moe, which can be described as affection, attraction, or love for anime and manga characters. It is typically the otaku who experiences moe, the otaku being an individual who indulges (often obsessively) in subcultures rooted in Japanese anime and manga. The word moe has been self-generated by the otaku community over the past two decades and is a linguistic transformation of the Japanese words meaning “to bud” and “to burn.”² I am interested in the derivative content produced by these anime fans and the resulting changes to the nature of authorship and artistic content. For that reason, I took on the form of a “mad movie,” a “short video clip created by capturing the screens of anime and games and manipulating and editing them to music, mainly circulated over the Internet.”³

Madder Movie operates as an academic inquiry into a contemporary anthropological phenomenon while also contributing to the otaku tradition of making “mad movies”—that is, it acts as an outside critique while also engaging my personal feelings as a member of the otaku community.

II. Step 1: “Build your database”

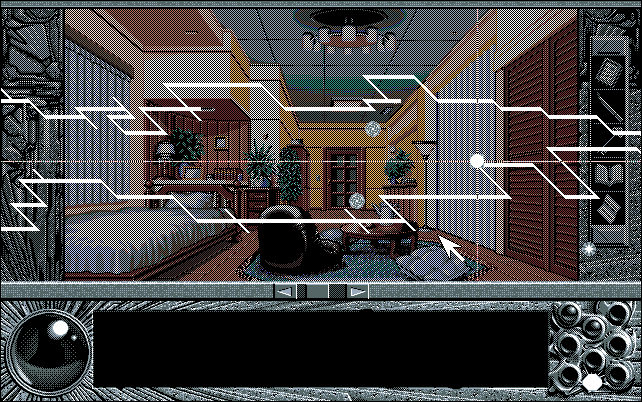

Opening sequence of Madder Movie

Azuma Hiroki in his 2009 book Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals (which in no small part inspired Madder Movie) outlines the concept of the “loss of the grand narrative.”4 The concept narrows in on otaku in postwar, postmodern Japan, on how these individuals no longer consume anime film and series as totalities within themselves.5 Instead, many otaku identify the components and fragments of anime (bunny ears, antennae-like hair, maid costumes) that make them feel moe and seek out all the instances of those fragments, compiling them into a database—be it psychological, digital, or material. This database condition is reflected in Madder Movie’s aesthetic sensibilities as a pure white landscape, not unlike the white walls of an art gallery, upon which the fragments are projected and displayed.

The film opens with a catalog of images that flicker one by one down the screen, accompanied by an arpeggiating synthesizer which further suggests the accumulation of data over time. This forms a large grid, or database, of screenshots of Bishōjo games, also known as “beautiful girl games” or, as Azuma refers to them, “novel games.” These novel games, drawn in the anime style and popularized in the early 1990s, often take the form of dating simulators targeted toward a young Japanese audience of male otaku. In almost every game, the player is faced with the same type of formatted image—a beautiful girl looking at them, composited onto a background, with lower-third text prompting the player with dialogue or a handful of decisions to choose from. If the player makes enough correct decisions, the beautiful girl’s affection for them increases. Pornographic images may appear as a reward, and other young, beautiful women can be “unlocked.” Although there are many subcultures of anime and manga that focus on alternative gender and sexual identities, the majority of novel games cater to the heteronormative, male-centric cultivation of moe.

In the opening of the film, the viewer is presented with a grid of screen captures before the following “sliding sequence” of screenshots begins.6 A significant component of Azuma’s argument includes his concepts of a “surface outer layer” and a “deep inner layer,” these layers being what is left following the “loss of the grand narrative.” Rather than a grand narrative that follows a linear timeline, novel games alternatively offer up discrete elements and images to be selectively sorted and databased by the player. Using the novel game Yu-No as an example, Azuma calls the actual gameplay of making decisions and talking to the beautiful girl the “surface outer layer” or “the drama” of the game. The different timelines through which the story can progress, depending on the player’s decisions, constitute the game’s “deep inner layer” or “system.” Screenshots exemplifying these two layers are depicted below.

The “surface outer layer” or “drama”

The “deep inner layer” or “system”7

There is a tension between these two layers that is essential to understanding the difference between the way an otaku consumes content and the ways in which narrative content is traditionally consumed. The novel game exemplifies the otaku as an activated consumer: the player bypasses the mirage of the grand narrative, hopping around the timelines of the game structure to consume the images they desire with no need to follow a predetermined storyline. Otaku understand that all media is available to be deconstructed into its requisite elements and reassembled into a mad movie or any other format which fits their narrative or romantic desires. While the mad movie deploys an assemblage of mixed media to fulfill the desires of the otaku, Madder Movie appropriates this technique with the project of revealing this mode of narrative consumption itself.

With the grid of screen captures in Step 1 and the generous use of white space throughout the film, Madder Movie acknowledges the separation between the “surface outer layer” and the “deep inner layer” as well as the moments of their interaction. There are shards of intense emotion or “drama” scattered throughout Madder Movie, but the presence of “the system” (in this case, “the Video Editor”) is always felt in the surgically precise execution of images formatted into frames and mobilized into “Steps” to generate a specific cinematic effect in a white void world.

Step 1 also features audio from an interview of Kon Satoshi, speaking on his 1999 anime film Perfect Blue—a film also interested in the blurring of reality generated by obsessive fan communities:

You sometimes feel like losing yourself in whichever world you are watching. Real or virtual. But after going back and forth between the real world and the virtual world, you eventually find your own identity through your own powers. Nobody can help you do this. You are ultimately the only person who can truly find a place where you know you belong.8

This interview audio is followed by an accumulating audio montage created with screenshots and audio pulled from Japanese ASMR videos on YouTube. ASMR, or autonomous sensory meridian response, is a physical response to certain sounds that feels like a euphoric tingling sensation moving from the scalp down the neck and spine. It is an incredibly pleasurable feeling and has an enormous online presence with dozens of communities centered around different genres of sounds. One popular genre includes the videos used to make the audio montage: Japanese women speak softly into a binaural microphone, comforting you after a long day of work, cleaning your ears, kissing you, or giggling. Significantly, the picture accompanying the audio of these Japanese ASMR videos is usually of a beautiful anime girl, not the person who recorded the audio. Instead you imagine it is the anime girl whispering to you, kissing you, and cleaning your ears. There is something both calming and sinister about the public’s open access to such private and intimate audio separated from the face behind the voice. Mid-montage in Madder Movie, there is a jarring change in music from the tones of the arpeggiating synthesizer to a choral landscape punctuated by uneasy strikes of percussion, acknowledging through sound how quickly one’s perceptions of ASMR might transition from calm to sinister.

Typical American ASMR, video of YouTuber9

Typical Japanese ASMR video, static photo of anime girl10

Thomas Lamarre in his book The Anime Machine analyzes the sliding cel-animation that produces the iconic motion of anime, likening this to the transverse view out of a train window and dubbing the slippage of composited layers the “animetic interval.”11 The animetic interval is a key conceptual driver of Madder Movie, as it is the technique that transforms anime from a stack of static two-dimensional drawings on celluloid paper into the enlivened reality of animated video, simulating the three-dimensional reality of live- action film while retaining the memory of its requisite components of sliding two-dimensional drawings. By animating screenshots across a background of receding ASMR YouTube screen captures, Madder Movie crudely replicates the animetic interval, pulling the viewer’s eye across the surface of the screen and simulating three- dimensionality. The inclusion of Kon Satoshi’s interview and the ASMR audio montage is my acknowledgment of the many transmedia layers that contribute to the anime world of moe which interests me.12

III. Step 2: Blur the real and the virtual

Step 2 begins with a quote Ian Condry’s book The Soul of Anime, from chapter seven, “Love Revolution.” The quote explains how a petition was started in 2008 to legalize the right to marry an anime character. Next to it is a screenshot of a company’s promotional photo advertising their ability to provide marriage certificates for clients and their anime wives (“waifus”) of choice. For many, the desire to marry an anime character may sound absurd, eliciting a value judgment on otaku as individuals suffering from mental illness or misanthropy. While this specific manifestation of moe does indeed shed light on a psychological condition, it is a phenomenon that must be reflected upon with nuance:

For some writers, moe constitutes a “love revolution” – that is, an example of pure love and a logical extension of the shift from analog to digital technology. For another theorist, moe symbolizes a postmodern, “database” form of consumption… the editors debate the idea that what moe offers is “pure love” (jun’ai) that exceeds what can be had with real women.13

The desire to marry anime characters is obviously an extreme example of moe but illustrates how moe is capable of blurring the real and the virtual— an idea that comes up again and again in scholarly discourse on Japan following its 1990s economic recession.14 Iida Yumiko writes extensively on how the recession of a postwar, America-installed, bubble economy in Japan triggered a collapse of national identity. As a result, many young Japanese individuals, rather than abandoning postwar modes of capitalist consumption, instead perpetuated these modes of consumption, searching for meaning and identity not in nationalism or traditional Japanese culture but in the fantasy worlds of manga and anime.

The following quote from Azuma frames the second section of Step 2 in Madder Movie: “Once the otaku are captivated by a work, they will endlessly consume related products and derivative works through database consumption.”15 This section of the film examines perhaps the single most popular moe-inducing character, Hatsune Miku. Miku is the most popular Vocaloid (a singing software that features accompanying “idols” that more or less exist as virtual anime pop stars), and as a result is featured in a diverse range of media for fan consumption.16 The attached screenshot features the Hatsune Miku Domino’s Pizza app, the “Redial” music video, a fan’s collection of Hatsune Miku figures, a 3D choreography-rigged model of Miku, a dance-troupe of cosplayers all dressed as Miku, a Miku concert in Kansai in 2013, a makeup tutorial on how to look like Miku, and an unboxing video of a large-scale Miku Doll.

Hatsune Miku sequence in Step 2 of Madder Movie

Hatsune Miku is only one example of how the blurring of the real and the virtual in cultures of moe and anime fandom has become increasingly centered around characters rather than narratives. Otsuka Eiji in his essay “World and Variation: The Reproduction and Consumption of Narrative”17 expands upon Jean Baudrillard’s concept of an economy built on images and signs, positing that consumers now accumulate small pieces of a larger narrative, be these episodes of an anime series, plastic figurines, or live concerts.18 The moe that Hatsune Miku generates for her fans does not exist in a standalone piece of media but in an entire universe of transmedia which fans respond and contribute to. This is precisely why I found Hatsune Miku essential to include in the investigation of moe as a phenomena that is perhaps emblematic of a more general contemporary condition in which the distinction between virtual media and material media has been collapsed.19

IV. Step 3: “Fall in love”

Step 3 begins with an artificial voice saying “press play,” with a virtual MIDI choir singing these same words repeatedly in the background. The music, like the music in the ASMR section of Madder Movie, establishes a calming yet digitally nefarious atmosphere for the film’s video content, alluding to the darker truths that may lurk behind the bright, virtual images of anime. For Step 3, I used footage of paint strokes from a database of video clips I created with New York-based artists Danielle Stolz and Bernhard Fasenfest. We filmed dozens of different gestures using green acrylic paint. The green was used as an independent alpha channel, keying in footage of moe-inducing anime characters juxtaposed with videos of crying Japanese men in a kind of “video painting.” It was important to include these video paintings in order to inject Thomas Lamarre’s idea of the animetic interval with a new element of dimensionality and transmedia.

Video painting from Step 3 of Madder Movie

These video paintings emphasize the profound nature of moe as a personal, sincere, and visceral emotional response, instead of its common perception as a perverted or sexually deviant social phenomenon. The design of Bishōjo games are specifically concentrated on triggering such strong love and empathy for the “beautiful girl” character that the player will burst into tears. Crying as a standard otaku response to feeling love for an anime character itself warrants an investigation into the status of masculinity in relation to moe, a topic I may address more specifically in the future.20 Azuma below defends otaku who feel sexual moe:

Since they were teenagers, they had been exposed to innumerable otaku sexual expressions: at some point, they were trained to be sexually stimulated by looking at illustrations of girls, cat ears, and maid outfits. It takes an entirely different motive and opportunity to undertake pedophilia, homosexuality, or a fetish for particular attire as one’s own sexuality. On the one hand, otaku consume numerous perverse images, while on the other hand, they are surprisingly conservative toward actual perversion.21

Azuma’s quote is charged with an investigation of the image versus the actual. Can one really acknowledge and validate the subject whose sexual attraction prompts the consumption of the virtual image over the real, while also maintaining a confidence that this new sexuality does not run the risk of spilling over into a society that rejects these attractions? I allude to my stance on this problem in the final step.

V. Step 4: “Enjoy your new reality”

In Step 4 the viewer is immersed, first-person, in a “moe gallery,” a variety of geometries textured with video clips of female characters from anime films as potential triggers of moe.22 It was important that the final step of Madder Movie feature a break from the previously two-dimensional sliding frames of the previous steps into a three-dimensional space which the camera (and viewer) circulates through. Step 4 thus alludes to the optimism I feel toward moe’s blurring of the virtual and the real and its capacity to exist outside of the confines of the two-dimensional world. Ironically, this three-dimensional realm is still dominated by screens, albeit screens stretched across geometric canvases.23 The viewer floats through the gallery, eventually entering a chamber and ascending into a holy, light-soaked world, before settling back into a flat, two-dimensional frame as the following quote from Azuma is displayed and the credits roll:

This trying without success to go back from the visibles (small narratives, i.e., simulacra) to the invisible (the grand non-narrative, i.e., the database), and instead, slipping sideways at the level of small narratives is the structure of misfire that I call hypervisuality.24

The phenomenon of moe is often read as tragic. Otaku consume minute shards of emotion, categorizing them into a database to feel the raw emotion of love.

Elements of their affection slip in and out of the visible and invisible, the virtual and the real. It is in opposition to this tragic perception of moe that the conclusion to Madder Movie positions itself with less certainty and more optimism. Azuma’s definition of hypervisuality characterizes this “new reality” as one that cannot return to the old mode of existence (the “grand narrative” mentioned early in this essay). Though this definition is colored with a more defeatist perspective than mine, it was important for me to conclude the film with the idea that moe is precisely something that is hyper—something beyond, something that may never be fully understood, but only felt.

Moe gallery in Step 4 of Madder Movie

The writer would like to thank Marilyn Ivy, Department of Anthropology at Columbia University, for her guidance on this essay.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

NOTES

1. As noted in the credits of the film, music by One- ohtrix Point Never, Aaron David Ross, and James Ferraro were used. These three solo electronic musicians are known for compositional processes strongly reminiscent of the logic of mad movies in the way they rearrange audio samples with heavy-handed editing techniques to generate new worlds of emotion that are transcendent, glossy, and disturbing. It thus felt important to feature music that reflected the compositional and thematic aesthetics of mad movies and anime in the film.

2. Saito, Tamaki, Beautiful Fighting Girl (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 29. This linguistic origin is tied to the popularization of the anime series Sailor Moon. This origin is also covered in detail in Ian Condry’s The Soul of Anime (190-1). “The kanji character thus acts as a visual reference to the fact that the moe attraction is often bestowed on 2D characters who are on the verge of budding into young women.” This reference, in tandem with the often passionate, obsessive, or lustful qualities of the otaku “burning” for these characters, provides insight to the linguistic origins of moe.

3. Azuma, Hiroki, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals (Minneapolis: University of Minnestoa Press, 2009), 82. Mad movies take many forms, the most popular form being the Anime Music Video, or AMV. An AMV is a montage of clips of one or more anime series that often highlights key narrative arcs, fighting scenes, or romantic relationships between charac- ters. It is important to note that romantic relation- ships that may not have existed in the anime series are often created in AMV’s through the suggestive juxtaposition of clips and use of video filters and slow-motion, satiating fan-demand for romantic relationships in a phenomenon known as “shipping.”

4. For the purpose of this essay I will refer to the names of Japanese scholars and artists in the Japanese style: Last name, First name.

5. This idea calls to mind the “totality” in Claude Levi- Strauss’ book Myth and Meaning, in his decoding of fragments of images across Pan-American myths, suggesting that signs only reveal their meaning when read in conjunction with all myths in the region. Otsuka Eiji in his World and Variation: The Reproduction and Consumption of Narrative also breaks down the “totality” in the context of narrative consumption in Japan.

6. It is also not insignificant that for this sequence (and for that matter the entirety of Madder Movie), I had to participate in this very “databasing” technique myself in the searching, saving, and compiling of all the source content in a very short timespan, further supporting the idea of this film being somewhat accelerationist in being “Madder” than a “Mad Movie.”

7. University of Michigan, Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. “GameBase Wiki for the EECS 494: Computer Game Design course at the University of Michigan.”

8. Kon, Satoshi, Perfect Blue Interview with Director-Satoshi Kon.wmv (YouTube: GSTON319’s channel, 2010), 9:20.

9. Use of screenshot permitted under Creative Commons Attribution License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v-gu5VmQAwpRw

10. Use of screenshot permitted under Creative Commons Attribution License. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CyirKvHOOyo

11. Thomas Lammare, The Anime Machine (Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 7. “Sliding celanimation” refers to the traditional method of creating anime, which involves the drawing of characters and backgrounds onto transparent celluloid sheets, which are then layered, the sliding of these layers being filmed to simulate motio. Lamarre specifically positions the “animetic interval” in opposition to Western styles of animation which he dubs “projectile motion,” where the viewer moves through three-dimensional space, whereas in anime, the motion is much more two-dimensional, based on the transverse sliding of layers.

12. I think here of Kuge Shu’s essay “In the World that is Infinitely Inclusive” and his concept of “world” or “sekai” as something that is constituted by connection or love between people. While Kuge thinks about this in the context of Shinkai Makoto’s film “Voices From a Distant Star,” the idea is extremely compatible with the idea of the shared world in which otaku and anime fans who feel moe exist, distance deleted by the intimacy of the internet and the screen.

13. Ian Condry, “Love Revolution” in The Soul of Anime (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013), 192.

14. Iida Yumiko, Between the Technique of Living an Endless Routine and the Madness of Absolute Degree Zero: Japanese Identity and the Crisis of Modernity in the 1990s (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000).

15.Hiroki Azuma, Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009), 105.

16. Hatsune Miku also gives live performances, goes on tour, features in music videos, etc.

17. Otsuka, Eiji and Marc Steinberg, “World and Variation: The Reproduction and Consumption of Narrative” in Mechademia, Vol. 5, Fanthropologies (Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 104. It’s been said that Azuma Hiroki is indebted to the scholarly foundation established by Otsuka Eiji on these topics.

18. An essential part of Otsuka’s essay is the phenomenon of Bikkuriman chocolates, which came with stickers. The more chocolates that children bought, the more the stickers began to form an intelligible narrative, a narrative that can be expanded by the users themselves, an early suggestion of the phenomena of fan-derivative anime works and mad movies.

19. The character of Digiko in Di Gi Charat is also an incredible example of this character-driven moe replacing the former standalone film or series-based moe, and is covered in p. 39-44 of Azuma’s Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. An early image of Digiko was released to the public, and as a result hundreds of animations, manga, and drawings of Digiko were made by fans before any official content was ever released.

20. In thinking about subverted gender and sexuality in the context of moe and anime, I point to the University of Tokyo’s Patrick W. Galbraith’s paper “Bishojo Games: ‘Techno-Intimacy’ and the Virtually Human in Japan.” Galbraith puts pressure on the idea that Bishojo games are only a way for men to reaffirm masculinity and exert control over objectified woman-objects, instead reflecting on the woman as an abstracted, unattainable object of desire, the unattainability of which is fully known by the player. “It is increasingly difficult to talk about a strictly ‘male’ subject position, gaze or mode of desiring” particularly because the games themselves encourage identification with the expressiveness of the female characters, the male character conversely bodiless and left with less control than one would imagine.

21. Azuma, Otaku, 89.

22. Again, I hope pursue research on the implied heteronormativity of this scene in further critical research with the seriousness and meditation that such an investigation demands.

23. I experimented with making the walls, floor, and ceiling themselves textured with moe footage but the results were so disturbing that I felt it not fit the “deep inner layer” system of white space used in the rest of the film to suggest the uneasy but generally optimistic attitude I hold toward an often villainized phenomenon.

24. Azumai, Otaku, 105.

____________________________________________________________________________________________

WORKS CITED

Azuma, Hiroki. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Condry, Ian. “Love Revolution” in The Soul of Anime. Durham: Duke University Press, 2013.

Galbraith, Patrick W. Bishojo Games: “Techno-Intimacy” and the Virtually Human in Japan. Tokyo, University of Tokyo Press, 2011.

Kuge, Shu. “In the World that is Infinitely Inclusive: Four Theses on ‘Voices of a Distant Star’ and ‘The Wings of Honneamise’” in Mechademia, Vol. 2, Networks of Desire. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007.

Lamarre, Thomas. The Anime Machine. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Levi-Strauss, Claude. “The 1977 Massey Lectures” in Myth and Meaning. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1978.

Kon, Satoshi. Perfect Blue Interview with Director-Satoshi Kon.wmv. Youtube: GST0N319’s channel, 2010.

Saito, Tamaki. Beautiful Fighting Girl. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

Yumiko, Iida. Between the Technique of Living an Endless Routine and the Madness of Absolute Degree Zero: Japanese Identity and the Crisis of Modernity in the 1990s. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.